Adam Walker, David Fideler and LaMonica Curator have recently published on a “new Renaissance,” which they predict will soon materialize, each offering his or her own criteria for judging the occasion from past examples. These examples are selected across centuries, giving an impression of great historical competence, yet their prediction conflicts not only with the examples but with itself. I am neither an historian nor any kind of specialist of the Italian Renaissance, but having read some on the topic I am nonetheless unable to reconcile their views with my experience. What these three propose moreover appears less history than allegory, in which decadence of culture is succeeded, necessarily, by renewal, a proposal that also conflicts with the historical consciousness of those same humanists on whose behalf they claim to relate. My concern is primarily with Walker and Fideler, who present themselves as authorities on the Renaissance. They do this by selling courses on the subject that position them as experts, by emphasizing their credibility through frequent plugging of academic credentials, and by stating, unequivocally, the factual basis for their pronouncements even where it disagrees with both the source material and scholarly consensus in such a way that no one without familiarity with either can be expected to know the difference. I have included LaMonica to emphasize that these predictions of a new Renaissance are incompatible, and that only by disregarding historiography can the predictions of Walker and Fideler be made imprecise enough that the incompatibility between them is ignored.

Of the more obvious reasons for skepticism is Walker’s dating of the “European Renaissance” to the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, and his subsequent claim that it was “partly initiated by the Fall of Constantinople in 1453.”1 The latter claim would mean that the only cause worth mentioning occurred three quarters of the way through the event it initiated. At least part of the problem is that the dating of the Renaissance is truncated. Standard introductions to Renaissance humanism in its entirety begin with the fourteenth century and end with the seventeenth century. Charles G. Nauert’s Humanism and the Culture of Renaissance Europe is one prominent example, and it begins by further complicating Walker’s narrative that the Fall of Constantinople was responsible for renewed interest in Greek by pointing out that

Western Europeans could have recovered Greek language and literature in the thirteenth century as easily as in the fifteenth, but they did not seize the opportunity. The scarce Latin manuscripts that humanists of the early fifteenth century took pride in ‘rediscovering’ were all available during the high-medieval period, but they were not ‘discovered’—that is, few readers knew of their existence. In the case of both classical Latin and Greek, something had changed between the early thirteenth century and the early fifteenth century. This change was a change of mentality, of values, that made the tedious mastery of the classical languages and diffusion of classical texts seem worth the effort.2

Something like a new mentality, but one localized to Florence, is discernable from Walker’s engagement with Marsilio Ficino, but the implication that “stale scholasticism” was its cause is wrong.3 Of the four cities that Walker mentions as centres of scholastic dominance, two were recent additions. “After some earlier appearance at Salerno and Naples,” explains Paul Oskar Kristeller, “Aristotelian philosophy became for the first time firmly established at Bologna and other Italian universities towards the very end of the thirteenth century, that is, at the same time that the first signs of a study of the Latin classics began to announce the coming rise of Italian humanism.”4 Scholasticism did not stale in Italy before the appearance of humanism, and complaints against it were not always from outside scholasticism. The nominalists shared complaints with the humanists, and there were scholastics who were also humanists. The decline of scholasticism did not begin until the late sixteenth century, and neither Ficino nor any other variation on Platonism or hermeticism posed a serious threat to scholasticism, which eventually succumbed by the seventeenth century to the natural philosophies of, among others, Galileo Galilei.

These details are a problem for Walker’s version of events because they show that the decline of scholasticism, which is the only explicit precedent he offers in support of overall cultural decline, did not take place for another two centuries, and without it he offers no sound criterion for judging cultural renewal imminent. There was a new emphasis on professional training in rhetoric that sustained the cultural turn to ancient Roman and, eventually, Greek texts, but, initially,

the men of the Renaissance returned to the pagans because they discovered types in their literature and art which expressed feeling similar to those which they wished to express. Thus it is the feelings first discovered in poetic experience which gave new meaning to classical rhetoric. The discovery of new texts is not innovating but symptomatic; it is not the finding of new texts so much as the fresh reading of them—of Cicero’s De inventione by Brunetto Latini, of Cicero’s letters by Petrarch—that matters; most of the major discoveries of the mature oratorical works of Rome come only later with Poggio’s discoveries in France and Germany and Bishop Landriani’s at Lodi (1416-1420).5

Situating humanism against scholasticism, or any other -ism, can be conceptually useful, but historically misleading, and it was not until the nineteenth century, “under the influence of Hegel, that the modern addiction to reifying ideologies and social trends using nouns formed from -ismos, the Greek suffix indicating nouns of action or process, began to take hold.”6 Walker’s inaccuracies appear the result of relatively recent historical habits, which would explain his frequent reading into Renaissance humanism a number of categories distinct to German Romanticism. The notion of Zeitgeist, however, tells us nothing about the imitatio of Petrarch, who’s historical consciousness was of a reserve of moral possibilities rather than of epochal succession.

In any case, Walker’s broader narrative whereby newfound Platonism broke its Aristotelian chains is long recognized a mistake:

The predominant view of historians was once that the philosophy of Aristotle, after spreading through Latin Christendom in the wake of the great wave of translations from Greek and Arabic begun around 1125, reached its greatest diffusion in the thirteenth century, came to a profound crisis in the fourteenth, and then suffered in the fifteenth under the challenge of Platonism. As a result, Aristotelianism in the Renaissance survived in only a few “conservative” strongholds—such as the universities of Padua, Coimbra, and Cracow—before it was finally swept away by the coming of modern philosophy and science. Thanks to the work of historians like John Herman Randall, Eugenio Garin, Paul Oskar Kristeller, Charles Schmitt, and Charles Lohr, research in the last sixty years has shown that such an image of the development of European thought is so one-sided as to be substantially false. The point here is not to insist on the notable expansion of Aristotelianism in the fourteenth century—for in that century, far from declining, Aristotelian philosophy reinforced its position by consolidating its fundamental role in university instruction, by linking its fate to that of influential philosophical and theological schools, and by obtaining for the first time the explicit support of the papacy. One must go still further and insist that, if the greatest intellectual novelty of the Renaissance was the rediscovery of little-known and forgotten philosophical traditions, Aristotelianism nevertheless remained the predominant one through the end of the sixteenth and into the seventeenth century.7

For Kristeller, the mistaken “view that the Renaissance was basically an age of Plato”8 began with historians, who,

like journalists, are apt to concentrate on news and to forget that there is a complex and broad situation which remained unaffected by the events of the moment. They also have for some time been more interested in the origins than in the continuations of intellectual and other developments. More specifically, many historians of thought have been sympathetic to the opponents of Aristotelianism in the Renaissance, whereas most of the defenders of medieval philosophy have limited their efforts to its earlier phases before the end of the thirteenth century, and have sacrificed the late scholastics to the critique of their contemporary and modern adversaries.9

Walker’s emphasis on newness and his fixation on Ficino suggest that the same mistaken view is now making the rounds on Substack. His inaccuracies may be symptomatic of growing pains of adapting to a new media, but they also seem to betray impatience with, if not hostility towards, history, which appears thematic across all three authors.

Discriminating elements of continuity from discontinuity is basic to historical accuracy. Fideler’s “two factors,” which hold the importance of declining literacy and enrollment in humanities programs as indicators for predicting a new renaissance, have little to do with the conditions of education during the emergence of Italian humanism.10 Literacy was rapidly expanding, and this “reflected, and was in part the cause of, a vast growth in Italian vernacular literature from the later thirteenth century.”11 Literacy in Italy flourished late compared to elsewhere in Europe because Italians “found it difficult to cast off the literary monopoly of Latin.”12 When Latin did find a larger audience, “[m]ost urban Italians sought literacy for practical motives. They needed to keep business accounts, have some understanding of legal documents written in Latin by notaries, and on occasion even write business letters.”13 Mass literacy preceded any disgust felt by humanists towards the attenuated “human spirit” and this feeling could find expression and influence only within a system of education with the vulgar resources to provide it a place.14 The situation of early Renaissance humanism resembles more the state of universities with an aptitude for what Fideler disparagingly refers to as “theory,” which departed from the scholasticism of the new critics.15 This would, of course, upset Fideler's picture of a present cultural decline since it would locate a renaissance during what he characterizes as our dark age. The “intellectual frameworks and ‘theory’” he rejects, without argument, would then figure in better as representatives of cultural renewal.16

Yet Fideler’s inaccuracies are not only a problem of continuity and discontinuity but of reference, as facts seem to lose their way in his narrative:

As Walker notes:

Nearly every renaissance has begun under conditions of collapse or shortly after cultural exhaustion and the lack of meaning. And, like the European Renaissance of the fifteenth century, the next one will come from outside of the academy.

This is historically true. The original Renaissance humanists created the studia humanitatis — “humane studies” or the original humanities — outside the university system, which was then dominated by medieval scholasticism.17

The studia humanitatis was neither a creation of the Renaissance nor reinvented in the fifteenth century. The term was “used in the general sense of a liberal or literary education by such ancient Roman authors as Cicero and Gellius, and this use was resumed by the Italian scholars of the late fourteenth century.”18 This may come off as pedantic, but these inaccuracies accumulate and through repetition allow Fideler to blend history into an allegory more agreeable to Walker’s narrative. One original representative of the Renaissance, Ficino, then stands indiscriminately next to another, Petrarch, and despite their living a century apart an apparently joint contribution between them is presented with the semblance of historical legitimacy.

Fideler’s “historical” habits take after those he cites, including Michael R.J. Bonner, who’s In Defense of Civilization revises the broad strokes of history as an allegorical struggle between civilization and barbarism, “the sort of historiography in which the particular and the minute are dissolved within deep currents and long-term trends.”19 Bonner’s “purpose” (there is no thesis) “is threefold: to explain what makes civilization what it is, to show what we are in danger of losing in the event of collapse, and to point the way toward renewal.”20 We are, according to Bonner, obsessed with novelty, such that the past, and the possibilities it offers, are concealed from us. He advises that “[e]ach generation must seek facts, narrative, and and truth in the past.”21 Bonner wants to renew grand narratives, but does “not believe that the postmodernist era has ended, for the scepticism of grand narratives is alive and well and still justifies some of the most important of contemporary beliefs.”22

Bonner’s representative man of our postmodern era is Jean-François Lyotard, and The Postmodern Condition is his exclusive source for summarizing postmodernity. “The term ‘postmodern’ had been used before [The Postmodern Condition] in reference to art,” he explains, “but Lyotard was first to apply it to Western culture in general.”23 Bonner’s reconstruction of “[t]he basic argument” of the book begins

that the big ideas of the past, particularly the recent past, had led only to disappointment. Progressive movements of any kind—science, religion, the old ideologies, and especially Marxism—had failed to usher in the utopias that they had promised. No one believed in them, and no one could even agree on reality anymore because no one understood it. Here Lyotard’s limited understanding of chaos theory appeared to justify his claims. We could not look to universal theories or narratives to tell us who we are, or what purpose is, because they had led only to failure.24

This reconstruction is not, however, the argument of The Postmodern Condition, and there is every indication that Bonner never read the book. Lyotard’s thesis or “working hypothesis is that the status of knowledge is altered as societies enter what is known as the postindustrial age and cultures enter what is known as the postmodern age.”25 Bonner’s claim that this was the first use of the term “postmodern” in this way was probably lifted from the Wikipedia article, which cites Perry Anderson’s The Origins of Postmodernity, a book that Bonner never mentions. Anderson’s claim, moreover, is doubtful. It follows an account where

the first philosophical work to adopt the notion was Jean-François Lyotard’s La Condition Postmoderne, which appeared in Paris in 1979. Lyotard had acquired the term directly from Hassan. Three years earlier, he had addressed a conference in Milwaukee on the postmodern in the performing arts orchestrated by Hassan.26

But the term was already used in Legitimation Crisis, where Jürgen Habermas’s notion of postmodernity is the apparent model for Lyotard’s thesis:

The interest behind the examination of crisis tendencies in late- and post-capitalist class societies is in exploring the possibilities of a “post-modern” society—that is, a historically new principle of organization and not a different name for the surprising vigor of an aged capitalism.27

Lyotard cites Legitimation Crisis in the original German and directly responds to its argument at the end of The Postmodern Condition, and one can assume that Anderson’s confusion is a result of competing evidence for the original notion. But Bonner provides no such evidence, which suggests not only that he did not come to the claim alone but that he also did not come to it by way of Anderson. In all probability, Bonner found it on Wikipedia.

Skip this section of nine paragraphs if you do not want to read an attempt to interpret The Postmodern Condition as an extension and modification of humanism. It contributes but is expendable to the larger point of the essay.

For Bonner’s Lyotard, “[i]nstead of grand narratives (or ‘metanarratives’, as Lyotard called them), all we had left were ‘language games’ and a fragmentary jumble of local and personal ‘small narratives’, which were mutually contradictory.28 This is also available from the Wikipedia article, but it does not say much about what Lyotard is doing, which is not entirely removed from a humanist complaining about scholasticism. Humanists employed antilogy, a method for considering “the same events from different points of view; the best antilogy derives from the slightest difference in presenting the givens of a situation, the greatest difference in conclusions.”29 This allowed them to proceed according to the best course of action without neglecting the particular actors. In a postmodern society, however, where actions are at risk of disappearing behind social processes, the best we can hope for is that these processes will factor in the slightest differences, and that the slightest differences will eventually result in the greatest difference. Lyotard’s localized narratives are based on René Thom’s postulate that “[t]he more or less determined character of a process is determined by the local state of the process.”30 For Lyotard, “it is possible—in fact, it is most frequently the case—that these circumstances will prevent the production of stable form.”31 That these differences avoid the best course of action is the point since the best course of action is the social process. For the humanists, “[t]he amoral techniques of rhetoric are used to express the amoral force of circumstance on principle […] The Humanist’s attraction to debate in utramque partem is a positive sign of a generosity and tolerance which rejects the arid disputations of the Scholastics as tautological.”32 Thus Lyotard transforms humanist antilogy into what he calls ‘paralogy,’ an attempt not to change postmodern society by finding consensus among the different sides of an issue but through local dissensus intended to steer social processes by way of linguistic acts.

Bonner’s claim that chaos theory provides Lyotard with his rationale for dissensus is found in the Wikipedia article, with Anderson cited as its source. Anderson is describing the “pragmatics of postmodern science” that Lyotard argues allow us to strategically avoid inappropriate demands of legitimacy.33 Modernity demanded that all knowledge share its standard of legitimacy with science, but crisis eventually struck “scientific knowledge, signs of which have been accumulating since the end of the nineteenth century,” representing “an internal erosion of the legitimacy principle of knowledge.”34 The “distinguishing characteristic” of the Enlightenment, its “emancipation apparatus” that sought to free humanity through its discovery of human laws, “is that it grounds the legitimation of science and truth in the autonomy of interlocutors involved in ethical, social, and political praxis. […] There is nothing to prove that if a statement describing a real situation is true, it follows that a prescriptive statement based upon it (the effect of which will necessarily be a modification of that reality) will be just.”35 According to Lyotard, “that is what the postmodern world is all about. Most people have lost the nostalgia for the lost narrative. It in no way follows that they are reduced to barbarity. What saves them from it is their knowledge that legitimation can only spring from their own linguistic practice and communicational interaction.”36

For Lyotard, legitimacy has over the course of centuries become too dependent on “the denotative game (in which what is relevant is the true-false distinction)” that offers rules of discourse appropriate to science.37 Science, he argues, is ambivalent, on the one hand independent of “the prescriptive game (in which the just/unjust distinction pertains)” and “the technical game (in which the criterion is the efficient/inefficient distinction)” in its pursuit of truth and on the other hand dependent on them to exist within society.38 Over several centuries, the denotative game has overwhelmed the prescriptive game, such that how best to act is lost to the calculation of action. Lyotard complains that “[s]ocial pragmatics does not have the ‘simplicity’ of scientific pragmatics. […] There is no reason to think that it would be possible to determine metaprescriptives common to all these language games or that a revisable consensus like the one in force at a given moment in the scientific community could embrace the totality of metaprescriptions regulating the totality of statements circulating in the social collectivity.”39 This renders traditional ethics meaningless, and Anderson is pointing out that “micro-physics, fractals, discoveries of chaos,”40 encourage Lyotard to see a way out of the demands of scientific legitimacy by imitating “incomplete information, ‘fracta,’ catastrophes, and pragmatic paradoxes” that he believes characterize the science of postmodernity.41

The everyday philosophical concerns informing The Postmodern Condition are classical in origin, and Aristotle’s identification in the Nicomachean Ethics of prudential action with the good life is as good a starting point as any. For Aristotle, prudence was “a true and reasoned state of capacity to act with regard to the things that are good or bad for man.”42 It is distinct from art, “which has an end other than itself,” and were prudence an art it would not be a virtue, “for good action itself is its end.”43 Prudence is a virtue, but one nonetheless closely related to the art of rhetoric, since the highest kinds of virtue “must be those which are most useful to others […] Prudence is that excellence of the understanding which enables men to come to wise decisions about the relation to happiness of the goods and evils that have been previously mentioned.”44 Aristotle’s ethical ideal is the rhetor who relates to others the good and evil of their actions.

Aristotle’s categories of good and evil are not universal but communal, and prudence must be learned through a particular community. Rhetoric is a powerful art for teaching good and evil because, where successful, it performs to the interests of the public, and it is the communal public where the categories of good and evil originate and thereby the source of what is prudent. Epideictic rhetoric, especially, which is the art of praise and blame, becomes an art of preserving the good of the community. During the Renaissance, “epideictic was taken over by that branch of moral philosophy concerned with human actions to be imitated or avoided; the link between the two disciplines was the concept of prudentia, which Sir Thomas Elyot, quoting Cicero, defines as ‘the knowledge of things which ought to be desired and followed, and also of them which ought to be fled from or eschewed.’”45 The basis for studying literature among the humanists became overwhelmingly a matter of praise and blame, such that “[i]n the most comprehensive work of literary criticism in the English Renaissance, The Art of English Poesie, usually attributed to George Puttenham (published 1589; but evidently written much earlier), the genres are again ranked according to their epideictic function.”46 It may well be that the rigid moralism so common in the contemporary humanities has its basis in epideictic.

For the humanist Leonardo Bruni, epideictic was the basis for “recurring types of civic virtue.”47 “Bruni’s historiography is the vehicle of neither particulars nor universals but types” that reflect his “rhetorical realism.”48 These types allow him to praise or blame characters or situations of the past as moral possibilities for the future through “a dimension of personal experience” that “works against radical ethical solipsism, for the sense of historical continuity in choice.”49 Bruni offers a typical course of action, neither universal nor particular to any community, but drawn from the exemplary standard set by historical success. The strategy employed in The Postmodern Condition is one where Lyotard explains that his description of society “makes no claims of being original, or even true. What is required of a working hypothesis is a fine capacity for discrimination. […] Our hypothesis, therefore, should not be accorded predictive value in relation to reality, but strategic value in relation to the question raised.”50 Bruni and Lyotard are distinct in the important respect that postmodern societies are historically unprecedented. For Bruni, classical literature always provided ready-made types. For Lyotard, “we are in the position of Aristotle’s prudent individual, who makes judgments about the just and the unjust without the least criterion.”51

Neither science, ethics nor history provide us with metaprescriptives for how to act. “For this reason,” Lyotard concludes, “it seems neither possible, nor even prudent, to follow Habermas in orienting our treatment of the problem of legitimation in the direction of a search for universal consensus through what he calls Diskurs, in other words, a dialogue of argumentation.”52 Lyotard proposes that “[t]he ability to judge does not hang upon the observance of criteria. The form that it will take in the last Critique is that of the imagination. An imagination that is constitutive. It is not only an ability to judge; it is a power to invent criteria.”53

Contrary to Lyotard, Habermas argues that reason can emancipate action from the confusions of postmodernity, but we have to first figure out the history informing it. “On the road toward science,” he argues that “social philosophy has lost what politics formally was capable of providing as prudence.”54 He reflects how “[p]olitics was understood to be the doctrine of the good and just life; it was the continuation of ethics.”55 For the Greeks, “politics referred exclusively to praxis,” and “[t]his had nothing to do with techne, the skillful production of artifacts and the expert mastery of objectified tasks. […] For Hobbes, on the other hand, the maxim promulgated by Bacon, of scientia propter potentiam, is self-evident: mankind owes its greatest advances to technology, and above all to the political technique, for the correct establishment of the state.”56 For Aristotle,

[t]he capacity of practical philosophy is […] a prudent understanding of the situation, and on this the tradition of classical politics has continued to base itself by way of the prudentia of Cicero, down to Burke’s “prudence.” Hobbes, on the other hand, wishes to make politics serve the secure knowledge of the essential nature of justice itself, namely of the laws and compacts. This assertion already complies with the ideal of knowledge originating in Hobbes’s time, the ideal of the new science, which implies that we only know an object to the extent that we ourselves can produce it.57

A revolution that began with “Machiavelli on the one side, by Thomas More on the other” that reached maturity in the scientific politics of Hobbes separated “politics from morality” by replacing “instruction in leading a good and just life with making possible a life of well-being within a correctly instituted order.”58 The praxis of politics had replaced ethical theory and its corresponding art of rhetoric with something closer to social science. Yet one can still recover the ancient political art in Lyotard, his denotative, prescriptive and technical games are a postmodern permutation of the genres of judicial, epideictic and deliberative rhetoric.

Unlike Habermas and Lyotard, Bonner simply ignores the changing conditions of praxis. This reflects his histography whereby the historical particulars and minutiae (i.e. actions) disappear behind “big history.”59 The rationale behind The Postmodern Condition and the argument itself are explained away as a unidimensional plot point in Bonner’s impractical narrative. Fideler apparently shares his ignorance, never responsive to, let alone innovating on, the practices and techniques enacted by the humanists whom he heralds as signatories of a new Renaissance. Thus how the Renaissance happened is less important to him than that it happened, and it is thereby reduced to spectacle.

End of section.

James Hankins is another historian informing Fideler’s views who has advocated moral renewal through eschewal of praxis. Hankins has been revising accounts of the Italian humanists for years towards the idea that “humanists of the early Renaissance avoided ideological confrontations over constitutional forms, preferring to direct their reforming energies at improving the virtues of the ruling class. Their reforms were generally about governors, not governments.”60 This recently came to a head with the publication of Virtue Politics, in which

[t]he expression “virtue politics,” as those familiar with modern philosophical ethics will recognize, is meant to recall the term “virtue ethics.” The latter is an approach to moral philosophy, usually said to descend from Aristotle, that has been revived in the modern academy by philosophers such as Elizabeth Anscombe, Bernard Williams, Alasdair MacIntyre, and Julia Annas. In contrast to the other two leading approaches to normative ethics in the modern world—deontology and utilitarianism—virtue ethics emphasizes the need to develop, through reflection and practice, excellent patterns of conduct (the virtues) so as to achieve the human good and human flourishing (eudaimonia, or happiness). It thus distinguishes itself from other ethical theories that are more concerned with (1) defining norms of practical action, or duties, based on maxims common to all rational beings, as in Kant; or (2) elaborating rules to be followed by a subject who judges the moral value of actions primarily by their consequences, that is, their capacity to maximize goodness, as in the case of the utilitarians. “Virtue politics,” by analogy with virtue ethics, focuses on improving the character and wisdom of the ruling class with a view to bringing about a happy and flourishing commonwealth. It sees the political legitimacy of the state as tightly linked with the virtue of rulers and especially their practice of justice, defined as a preference for the common good over private goods—their “other-directedness” as a modern might put it.61

According to Hankins, “[t]he humanist conception of the path to virtue—how one acquires virtue—stands in contrast with Aristotle’s. Whereas Aristotle saw the acquisition of virtue as a matter of practice, philosophical reflection, and habit, and aided by good birth, wealth, good upbringing, and good friends, the humanists as a rule see liberal education—full stop—as the path to virtue.”62 Classical literature furnished this education by instilling “noble mores, ingenui mores, and practical wisdom, prudentia—all the qualities needed for excellence in government.”63 The belief was that “[e]ducators who taught the humanities were thus performing a public service. By training the elite in the humanities, noble virtue would radiate down to the populace in general, who would benefit from and imitate the wisdom and moral excellence of their leaders.”64

For Hankins, leaders should be selected meritocratically, and education is not a matter of merely educating those born into privilege. He reflects that “[a] claim to superior wisdom and virtue is not so easily verified as a claim to be the legitimate heir or a magistrate duly elected in accordance with constitutional procedures.”65 Classical literature provided training in rhetoric, and while “[v]irtue was the key; only the charisma of virtue gave a leader the power to change the human heart, to bring order, peace, and willing obedience.”66 Those most eloquent were positioned to make changes from the top-down, and “[i]f some commoner were to show merit and practical wisdom he could always be taken into the ruling group (a practice sociologists call ‘sponsored mobility’). This was in general the practice of Renaissance republics too: deliberation was confined to the well informed, whereas the people in their councils were only allowed to vote up or down on legislation formulated by their betters.”67

As to who decides merit, the Italian humanists discovered that they were ideally situated. Yet something like cult of expertise is being suggested by Hankins, and it is not difficult to confirm this from the humanists themselves. Desiderius Erasmus advised that “it is not enough just to hand out the sort of maxims which warn” the prince “off evil things and summon him to the good. No, they must be fixed in his mind, pressed in, and rammed home.”68 One gets a sense that the humanists aspired towards governing when for Giovanni Botero it seemed "necessary that the king never bring to the council anything for deliberation that was not first vetted in a council of conscience to which outstanding doctors of theology and cannon law belongs.”69 That something as personal as conscience should defer to expert educators suggests that princedom in either case is an empty title for humanist governors.

Hankins’s ‘meritocracy’ avoids the more provocative ‘aristocracy,’ from the Greek arete, or virtue, but this is more or less what he believes the liberal society ought to be today. He agrees

with Pareto that all government is oligarchical in the sense that all government implies the rule of a few over many. I think this was true even of Athens in its most democratic period in the late fifteenth century BC. The important questions are whether the political elites are opened or closed to merit (as the humanists advocated), and whether they are constituted by decent people of good character who accept a duty of care towards the poor and the powerless. Modern democracies are nothing like ancient ones and in practice resemble oligarchies; and they are yearly becoming less liberal. In modern Western societies small groups of the wealthy and powerful dominate government, the economy, and the wider culture (while talking incessantly of equality). It is still possible and, in my view, highly desirable to have a democratic check on ruling elites, but I believe, with the humanists, that, as things stand now, the best way to improve our governments is to improve our governors. The advantage of humanist virtue politics is that it is potentially compatible with modern pluralistic societies where citizens profess many faiths, including scientism and secular humanism, but also share common political institutions. For those institutions to function well, we need our societies to share at least a few common principles of practical reason—what Justus Lipsius called civil wisdom—as well as common models of what constitutes civilitas in Suetonius’ sense (Augustus 51-56), that is, the correct comportment of citizens. These standards are most likely to be widely accepted when derived from common traditions and from teaching common classical texts (not necessarily those of Greco-Roman antiquity).70

How merit would persuade an audience of ears conditioned by the GOPAC tapes is never explained, and some of his proposed solutions to social problems are poorly considered. He recalls that

while prosperity was a good thing, a mark of good government (as illustrated in the famous fresco in Siena’s Palazzo Communale), the humanists despised a life devoted to competitive money-making, driven by avarice. If there was to be competition among elites it should be generosa aemulatio, a noble rivalry in the best things, rivalry in human excellence or virtue. That too is a teaching of virtue politics that could profitably be revived today. Our democracy needs the right kind of competitiveness as much or even more than it needs equality. 71

Hankins’s belief that the problems of capitalism are resolvable through some version of trickle-down virtue is difficult to reconcile with the quality of his work as an historian.

Hankins’s forays into cultural criticism are no better. He appeals on behalf of the public good that “[p]olitical virtue requires that institutions of society and government be led by people who are able to make them function well—like the soul in the body, as Erasmus put it. This means recognizing what the ergon and the telos of the institution is: the way it should function (ergon) to best achieve its end or good (telos).”72 He laments “that our institutions are led by people who simply don’t care, or don’t appear to care, about the primary function and purpose of the institutions they lead. They have other teloi to pursue, other virtues to signal.”73 Hankins descries the experience at his university, Harvard, where “more or less every week the faculty receive an email blast from some self-important administrator, usually written in bureaucratic langue de bois, warning of some moral danger to the community.”74 The result of “[a]ll of this incontinent sermonizing” are the ‘scholar activists.”’ that apparently include “the declining quality of” many of his colleagues.75 Missing from the article is an account of Hankins’s understanding of the university. There is no self-criticism, no critical eye directed inwards and towards what his ergon and telos would look like in practice, or why his colleagues, and the faculty at other universities would approve of it. He appeals instead to the public for support on the basis of shared frustration.

In his review of Virtue Politics, Hannan Yoran singles out Hankins’s criticism that “[i]n recent historical scholarship it has become customary to present humanism as a movement principally concerned with language and style; engaged in the recovery and elaboration of ancient literary genres, methods, and textual practices; and preoccupied with antiquarian and philological questions. This interpretation in my view represents a confusion of ends with means, and reflects the priorities and sympathies of modern scholars more than it does the fundamental values and goals of the humanist movement.”76 Yoran asks “[w]hy not look at humanists both as promotors of virtue politics and as professional rhetoricians?”77 Hankins did so in the the past, but this distinction is now absent. One possibility is that Hankins may want to withhold the practices of his profession, and assure that those outside its walls that professors are competent to work them out to the advantage of a virtuous society. This would explain why his image of the university is unified, both individually and through their representation in Harvard.

I have dwelled on Bonner and Hankins because they seem to represent a turn among educated elites towards a history that resists criticism by those they believe socially inferior. Bonner received his doctorate from Oxford and Hankins from Columbia. Bonner is a former policy advisor for the Ontario Government now employed by the Aristotle foundation for Public Policy and Hankins is slated as visiting professor for the 2026-2027 school year for The Hamilton Center at the University of Florida, an institution established as part of Florida Governor Ron DeSantis’s efforts to undermine the woke agenda of universities. What they show is friendliness among elite universities towards political power beholden to donors. Bonner is the inferior historian, and if his historiography is any indication then he appears not to care much for history. Hankins does, but he either believes that donor interests cannot be stopped and that the best course of action is to mitigate the damages they inflict or he believes that he and others like him can genuinely ennoble them, and thereby all of us. In either case, as Erin Maglaque points out regarding his endorsement of charter schools, “[i]t won’t surprise anyone to know that the Christian nationalists and neoliberal free marketeers whose interests have coalesced in the cause of classical charter schools don’t actually care about Petrarch.”78

Fideler’s reverence for Petrarch as an icon of renewal avoids almost entirely the difficulty posed by material conditions. After briefly acknowledging that “programs are slashed for supposedly financial reasons” he cites as a counterpoint “Jennifer Frey’s honors program at the University of Tulsa.”79 What Walker admits tepidly as “insights” of critical theory would offer a fuller explanation of the problem, but one that would also pose a challenge to Fideler’s allegory of the spirit. Unlike Hankins, Fideler’s advocacy is not the result of deep insight into Renaissance culture. It resembles Spenglerianism, but in the register of American Transcendentalism, a closeted materialism preoccupied with the impurities of “demographic changes and a shrinking student population” while resolute that a symbolic solution be found.80 Consequently, Theodor Adorno’s criticism of Spengler is relevant to Fideler in that “[e]verything that cannot be reduced to a symbol of human nature, which, despite all his fatalism, Spengler endows with sovereignty, survives only in vague references to cosmic interconnections. […] By reducing history to the essence of the soul, Spengler gives it the appearance of a self-contained entity, yet one which for that very reason is actually deterministic.”81

The predictions of Walker and Fideler do not belong to the Renaissance. They belong to the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. These two write in the fashion of the manifesto rather than of anything composed by Petrarch or Ficino. Their arrangement of facts is pastiche united by a charge to “make it new.”

They claim that the Renaissance had to overcome the domination of scholasticism, as ours must overcome the domination of theory. That neither apparently know anything about either scholasticism or theory and therefore possess no idea how to resist domination by either is irrelevant because both believe that the true movement of history is on terms external to its facts, arranged into a language that they are peculiarly qualified to read (although they are happy to initiate others who support them financially). Yet if scholasticism is of no lasting importance to the Renaissance nor theory to us then what provides them with their awareness of a coming new Renaissance as opposed to more modest and regular developments in culture, or further domination by theory? The answer can only be that they believe themselves witnesses to events from a standpoint outside history. I gets the sense, as with popular cultural critics like Jordan Peterson, of observing a perverse spiritual journey, of something that should be private made public.

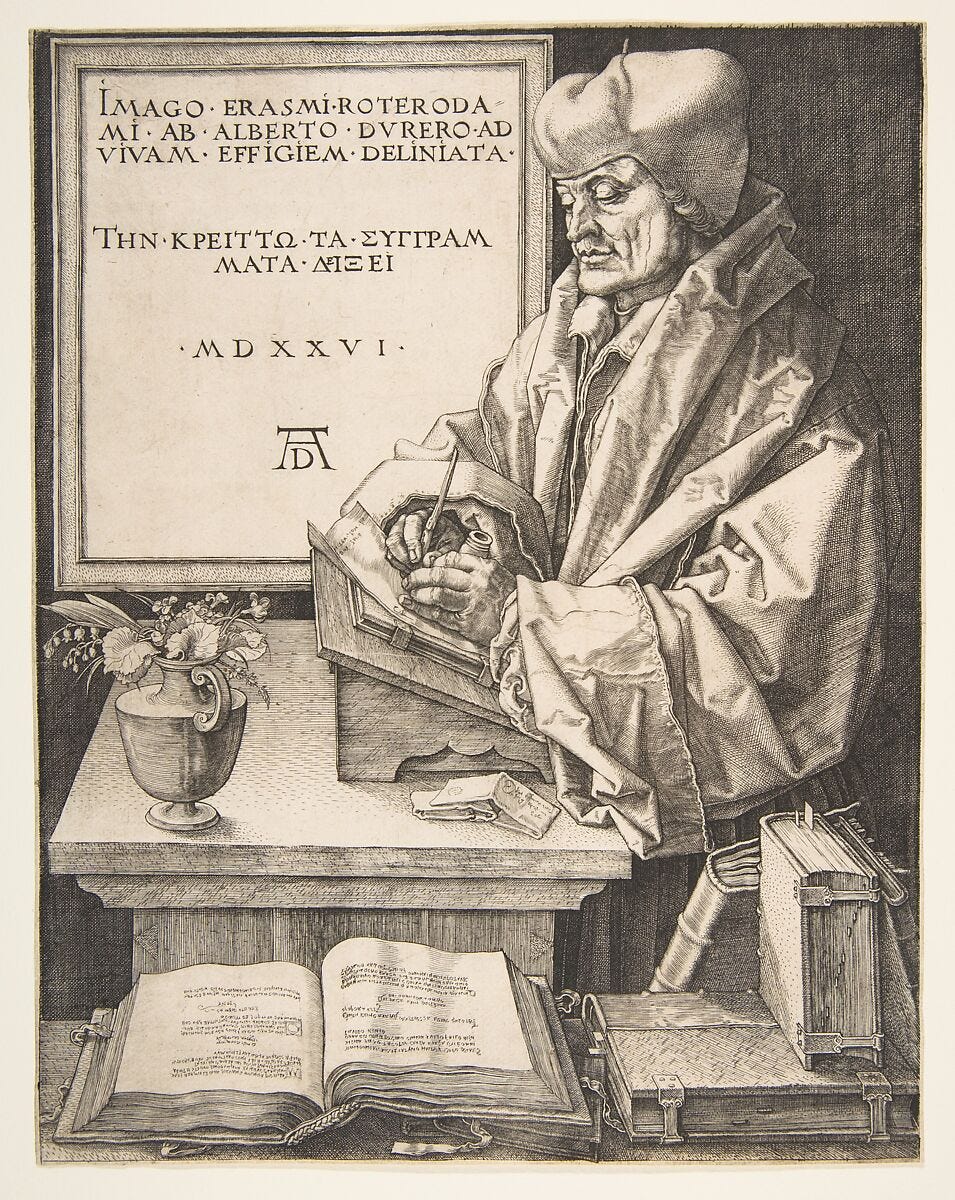

Apart from Fideler and Walker, LaMonica has proposed an alchemical model for predicting renaissances down to the decade. Her account of the Northern Renaissance, for example, retraces it as a visual arts movement embodied by Albrecht Dürer, whose contribution, as with Walker’s Ficino and Fideler’s Petrarch, is sui generis, although why he receives laurels while his contemporary Erasmus, who’s influence in education, theology, philology, and letters, and mastery over not only the printed page but the printing house, is displaced through reference to advocacy of “inner reform” suggests overreliance on the perspective of Art Historians. The idea, as far as I can tell, is that Dürer infused various arts such as printing with elements of Italian visual culture until a new visual rhetoric defined the North. “In this way,” she explains, “the Northern Renaissance becomes a hinge between medieval Europe and the birth of modern seeing.”82

But what about ways of seeing continued through to the Northern Renaissance that are not specific to Dürer or the visual arts? According to Ronald G. Witt,

[m]edieval grammarians and rhetoricians read the same ancient manuals of rhetoric and exploited the same ancient arsenal of colores rhetorici, as the humanists did. Medieval writers, however, often employed rhetorical colors to an extreme degree, whereas the early humanists, controlling their use of colores, more nearly approached ancient practice. They revived the simile, which had been neglected by medieval poets, and, by the 1360s, following the Ad Herrenium, they introduced ekphrasis (description) in their orations.83

Ekphrasis made its way North independent of the visual arts. Murray Krieger compares the non-mimetic uses of ekphrases from Jacopo Mazzoni to Philip Sidney and notes that “the image placed before our eyes by the words of the poet cannot be the same as the image placed there by the visual artist, just as the intelligible cannot be the same as the sensible.”84 Ekphrasis inspired Elizabethan culture through its appropriation by grammar schools, as “a gift to one’s masters or peers. Verbal paintings invite an audience to shuttle between aesthetic admiration and interpretive labor, a state of suspended attention a schoolboy could surely turn to his social advantage.”85

LaMonica is closer to the mark than Walker or Fideler in acknowledging cascading sociohistorical changes across Europe leading to the Northern Renaissance. Walker’s promise of a “more just and democratic society” through cultural renewal straightforwardly ignores the fundamentally unequal conditions of cultural participation in the past. Isotta Nogarola, for example, a brilliant student of Renaissance Italy, was a woman, and so, contrary to the prevailing humanist propaganda “that studies are an end in themselves,” she

failed to ‘achieve’, in spite of having access to humanist studies, as did others who failed to notice the tight inter-connectedness between the status of the bonae artes as a training and the political establishment and its institutions (other women, and those of inappropriate rank). Ad omne genus hominum, ‘for every type of person’, has to be read out as ‘for every appropriately well-placed male individual’. ‘Opportunity’, that is, is a good deal more than having ability, and access to a desirable programmed of study. It is also being a good social and political fit for society’s assumptions about the purpose of ‘cultivation’ as a qualifying requirement of power.

If humanism has been of its nature tightly ‘civic’, then as a woman Isotta Nogarola would never have had the support of the community of distinguished humanist scholars and teachers in her pursuit of humanist studies. But equally, if humanism had really set as its highest goal the pursuit of learning for its own sake, she would not have disappeared so decisively from secular scholarly view in the mature years of her life—years in which she continued to excel at those studies. She could continue an excellent student of humanism in private, but she could not be publicly supported as ‘virtuous’ in doing so.

What we are stressing is that the independence of liberal arts education from establishment values is an illusion. The individual humanist is defined in terms of his relation to the power structure, and he is praised or blamed, promoted or ignored, to just the extent that he fulfils or fails to fulfil those terms. It is, that is, a condition of the prestige of humanism in the fifteenth century, as Lauro Martines stresses, that ‘the humanists, whether professionals or noblemen born, were ready to serve [the ruling] class. The most apolitical of them could be drawn into the public fray’. The fortunes of a gifted woman embarked on the humanist training show vividly how a programme with no explicit employment goals nevertheless presupposes those goals, and how the enterprise of pursuing secular humanist studies can be regarded as morally laudable (a ‘virtuous’ undertaking) only where achieving that goal is socially acceptable.86

Walker and Fideler both pay tribute to our own exclusive models of achievement. Walker, for example, is always careful to specify that he holds not only a doctorate but one from Harvard, and although Fideler ingratiates himself to Walker by parroting the latter’s credentialed claim to credibility he leaves unnamed the source of his own doctorate from a less prestigious university, often associating it by proxy with time he spent studying at the University of Pennsylvania. In other words, and despite any pretense of modesty or calls for more egalitarian and inclusive education, both affirm the insubstantial but uncompromising exclusivity of university prestige that distinguishes those with the dignitas to publish on subjects like humanism from those without that dignity, the haves from the credentialess have-nots.

My suspicion is that the esoteric element in their writing serves a hidden purpose: any skepticism or disagreement that might arise towards or between the predictions of LaMonica, Fideler and Walker can be dismissed as an exoteric confusion. In practice, however, this enforces onto each of the predictions enough imprecision that skepticism or disagreement can be ignored, and it is difficult to see how they can be both predictive and imprecise at the same time (and predictive to a degree that all competing predictive models are put to shame).

In 1903, William James delivered a commencement speech at Harvard in which he distinguished between prestige “and something deeper and more rational” that departed from its “club sense”.87 According to James,

[t]he old notion that book learning can be a panacea for the vices of society lies pretty well shattered to-day. I say this in spite of certain utterances of the President of the University to the teachers last year. That sanguine-hearted man seemed then to think that if the schools would only do their duty better, social vice might cease. But vice will never cease. Every level of culture breeds its own peculiar brand of it as surely as one soil breeds sugar-cane, and another soil breeds cranberries. If we were asked that disagreeable question, “What are the bosom-vices of the level of culture which our land and day have reached?” we should be forced, I think, to give the still more disagreeable answer that they are swindling and adroitness, and the indulgence of swindling and adroitness, and cant, and sympathy with cant—natural fruits of that extraordinary idealization of “success” in the mere outward sense of “getting there,” and getting there on as big a scale as we can, which characterizes our present generation.88

James’s speech is laudatory, or else he might have also lingered on the more pessimistic implication that virtue is more difficult to sustain than vice, and continued with it to conclude that every institution eventually dies from vicious overabundance. Walker and Fideler do not represent the dying light of the university, but its coming death, which the university is now too weak to remedy. James recalls that “[t]he true Harvard is the invisible Harvard in the soul of her more truth-seeking and independent and often very solitary sons.”89 These sons will remain mostly solitary. It is their less solitary siblings who invoke truth on behalf of others that endanger the human spirit.

Revised 23 December 2025

Adam Walker. “Is the Next Renaissance Coming?” Adam Walker. https://adamgagewalker.substack.com/p/is-the-next-renaissance-coming. 8 October 2025. Accessed 16 December 2025.

Charles G. Nauert. Humanism and the Culture of Renaissance Europe. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2008 (1995), p. 10.

Adam Walker. “Is the Next Renaissance Coming?” Adam Walker. https://adamgagewalker.substack.com/p/is-the-next-renaissance-coming. 8 October 2025. Accessed 16 December 2025. What precisely constituted Ficino’s Florentine Academy is subject to considerable disagreement among scholars. See Robert Black’s “The Philosopher and Renaissance Culture.” The Cambridge Companion to Renaissance Philosophy. Edited by James Hankins, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2007, pp 21-26.

Paul Oskar Kristeller. “The Aristotelian Tradition.” Renaissance Thought and its Sources. Edited by Michael Mooney, New York, Columbia University Press, 1979, p. 41.

Nancy S. Struever. The Language of History in the Renaissance: Rhetoric and Historical Consciousness in Florentine Humanism. Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1970, p. 47.

James Hankins. “Humanism, Scholasticism, and Renaissance Philosophy.” The Cambridge Companion to Renaissance Philosophy. Edited by James Hankins, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2007, p. 30.

Luca Bianchi. “Continuity and Change in the Aristotelian Tradition.” The Cambridge Companion to Renaissance Literature. Edited by James Hankins, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2007, p. 49.

Paul Oskar Kristeller. “The Aristotelian Tradition.” Renaissance Thought and its Sources. Edited by Michael Mooney, New York, Columbia University Press, 1979, p. 33.

Ibid., p. 40.

David Fideler. “Could a New Renaissance Be Coming?” A Renaissance of Ideas. https://davidfideler.substack.com/p/could-a-new-renaissance-be-coming. 14 November 2025. Accessed 16 December 2025.

Robert Black. “Education and the Emergence of a Literate Society.” Italy and the Age of the Renaissance, 1300-1550. Edited by John M. Najemy, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2005 (2004), p. 19.

Ibid.

Ibid., p. 24.

David Fideler. “Could a New Renaissance Be Coming?” A Renaissance of Ideas. https://davidfideler.substack.com/p/could-a-new-renaissance-be-coming. 14 November 2025. Accessed 16 December 2025.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Paul Oskar Kristeller. “The Humanist Movement.” Renaissance Thought and its Sources. Edited by Michael Mooney, New York, Columbia University Press, 1979, p. 22.

Michael R.J. Bonner. In Defense of Civilization: How our Past can Renew our Present. Toronto, Sutherland House, 2023, np. (ebook).

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Jean-François Lyotard. The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. Translated by Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1997 (1984), p. 3. Lyotard’s “as is known” indicates that the term, as he used it, was already in use.

Perry Anderson. The Origins of Postmodernity. London, Verso, 1999 (1998), p. 24.

Jürgen Habermas. Legitimation Crisis. Translated by Thomas McCarthy. Boston, Beacon Press, 1975, p. 17. The word “postmodern” also appears in the German original from 1973, Legitimationsprobleme im Spätkapitalismus.

Michael R.J. Bonner. In Defense of Civilization: How our Past can Renew our Present. Toronto, Sutherland House, 2023, np. (ebook).

Nancy S. Struever. The Language of History in the Renaissance: Rhetoric and Historical Consciousness in Florentine Humanism. Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1970, p. 131.

Jean-François Lyotard. The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. Translated by Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1997 (1984), p. 59.

Ibid.

Nancy S. Struever. The Language of History in the Renaissance: Rhetoric and Historical Consciousness in Florentine Humanism. Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1970, p. 133.

Perry Anderson. The Origins of Postmodernity. London, Verso, 1999 (1998), p. 25.

Ibid., p. 39.

Ibid., pp. 39-40.

Ibid., p. 41.

Jean-François Lyotard. The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. Translated by Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1997 (1984), p. 46.

Ibid.

Ibid., p. 65.

Perry Anderson. The Origins of Postmodernity. London, Verso, 1999 (1998), p. 25.

Jean-François Lyotard. The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. Translated by Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1997 (1984), p. 60.

Aristotle. “Nicomachean Ethics.” The Complete Works of Aristotle (vol. 2). Translated by W.D. Ross and revised by J.O. Urmson, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1984 (1894), p. 1800 (6.5.1140b1-5).

Ibid.

Aristotle. “Rhetoric.” The Complete Works of Aristotle (vol. 2). Translated by W. Rhys Roberts, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1984 (1976), p. 2174 (1.9.1366b1-20).

Brian Vickers. “Epideictic and Epic in the Renaissance.” New Literary History. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, vol. 14, no. 3, 1983, p. 509.

Ibid., p. 508.

Nancy S. Struever. The Language of History in the Renaissance: Rhetoric and Historical Consciousness in Florentine Humanism. Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1970, p. 135.

Ibid., p. 136.

Ibid., p. 137.

Jean-François Lyotard. The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. Translated by Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1997 (1984), p. 7.

Jean-François Lyotard and Jean-Loup Thébaud. Just Gaming. Translated by Wlad Godzich, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1985, p. 14.

Jean-François Lyotard. The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. Translated by Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1997 (1984), p. 65.

Jean-François Lyotard and Jean-Loup Thébaud. Just Gaming. Translated by Wlad Godzich, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1985, p. 17.

Jürgen Habermas. Theory and Practice. Translated by John Viertel. Boston, Beacon Press, 1974 (1973), p. 44.

Ibid., p. 42.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid., p. 41, 43.

Michael R.J. Bonner. In Defense of Civilization: How our Past can Renew our Present. Toronto, Sutherland House, 2023, np. (ebook).

James Hankins. “Introduction.” Republics and Kingdoms Compared. Translated by James Hankins, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2009, p. xii.

James Hankins. Virtue Politics: Soulcraft and Statecraft in Renaissance Italy. Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2023 (2019), pp. 36-37.

Ibid., p 42.

Ibid.

Ibid., p. 43.

Ibid., p. 44.

Ibid., p. 49.

James Hankins. “Was Renaissance Virtue Politics a Failure?” The Good Society: A journal of Civic Studies. University Park, Pennsylvania State University Press, vol. 31, no. 1-2, 2022, p. 187.

Desiderius Erasmus. “The Education of a Christian Prince.” Collected Works of Erasmus (vol. 27). Translated by Neil M. Cheshire and Michael J. Heath, Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 1986, p. 210.

Giovanni Botero. The Reason of State. Translated by Robert Bireley, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2017, p. 63.

James Hankins. “Was Renaissance Virtue Politics a Failure?” The Good Society: A journal of Civic Studies. University Park, Pennsylvania State University Press, vol. 31, no. 1-2, 2022, p. 188-189.

Ibid., p. 193.

James Hankins. “Put Down the Woke Man’s Burden.” First Things. https://firstthings.com/put-down-the-woke-mans-burden. 25 August 2022. Accessed 18 December 2025.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

James Hankins. Virtue Politics: Soulcraft and Statecraft in Renaissance Italy. Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2023 (2019), pp. xv.

Hannan Yoran. “Virtue Politics and its Limits: A Review Essay.” The Historian. London, Taylor & Francis, vol. 84, no. 1, 2022, p. 63.

Erin Maglaque. “An Overabundance of Virtue.” The New York Review of Books. https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2023/09/21/an-overabundance-of-virtue-political-meritocracy-in-renaissance-italy. 21 September 2023. Accessed 18 December 2025.

David Fideler. “Could a New Renaissance Be Coming?” A Renaissance of Ideas. https://davidfideler.substack.com/p/could-a-new-renaissance-be-coming. 14 November 2025. Accessed 16 December 2025.

Ibid.

Theodor Adorno. “Spengler after the Decline.” Prisms: Essays on Veblen, Huxley, Benjamin, Bach, Proust, Schoenberg, Spengler, Jazz, Kafka. Translated by Samuel Weber and Shierry Weber, Cambridge, The MIT Press, 1967, pp. 68.

LaMonica Curator. “Pressure and Possibility.” LaMonica Curator. https://lamonicacurator.substack.com/p/pressure-and-possibility-is-a-sunday-reflections-by-lamonica-curator-presenting-an-in-depth-essay-about-the-elements-necessary-to-manifest-the-next-renaissance. 16 November 2025. Accessed 16 December 2025.

Ronald G. Witt. In the Footsteps of the Ancients: The Origins of Humanism from Lovato to Bruni. Leiden, Brill, 2000, p. 25. By “early humanists,” Witt has in mind humanists prior to Petrarch, going back as far as the twelfth century, and not specific to Italy.

Murray Krieger. Ekphrasis: The Illusion of the Natural Sign. Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992, p. 126.

Lynn Enterline. Shakespeare’s Schoolroom: Rhetoric, Discipline, Emotion. Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012, p. 37.

Anthony Grafton and Lisa Jardine. From Humanism to the Humanities: Education and the Liberal Arts in Fifteenth- and Sixteenth-Century Europe. London, Duckworth, 1986, pp. 43-44.

William James. “The True Harvard.” Writings, 1902-1910. New York, The Library of America, 1987, p. 1127.

Ibid.

Ibid., p. 1128.

You are quite hysterical. I enjoy this greatly.

You missed a top line word in my thesis—Possibility. There is no alchemy there, only a formulaic breakdown of the elements of what it might take. In conclusion, the possibility of what human choice and enterprise in our new world of ‘advancements’ might be.

You are right, of the group I am the benign one, merely setting up a historic review of Pressures and their resulting Possibilities. I’m not placing any bets.

Thanks for the traction! 😉